THE JOY OF MONKS AND PILGRIMS

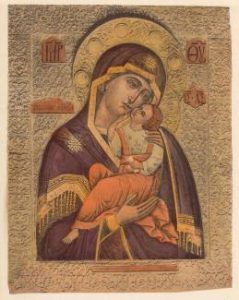

In the Monastery of Chevetogne there is a much loved and much venerated icon of the Mother of God of the Leaping Babe (Взыграние Младенца), painted in 1703 by Cyril Ulanov. It is displayed at the heart of the building opposite the former main entrance of the old house where, with its tender look, it welcomes all who find themselves at the monastery. It has always been known and venerated by the monks, at least since the early years after the Monastery’s foundation (1925), even if no one remembers exactly how it came to us. Older members of the community recall that when they were young they sang a Marian hymn before it every evening beseeching the Virgin’s help and protection while reaffirming their monastic vocation. Nowadays, the icon is carried once a year into the Byzantine church for the long vigil of the Acathyst Hymn to the Virgin celebrated on the Saturday of the fifth week in Great Lent. At such times the icon lives again before our eyes. The Mother of God appears in our hearts and we find ourselves inwardly resonating with joy that we too are children of God.

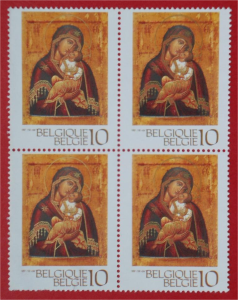

Belgian Christmas stamp (1991)

In 1991 the Belgium postal service published it on their annual Christmas stamp. In 2002 Father Denis Guillaume (1933-2008), hymnographer and indefatigable translator of liturgical texts, composed an office and an Acathyst for the icon in French.

The iconography of the Mother of God, in both the East and the West, varies greatly. Titles attributed to her from hymnography and popular piety are without number. The Leaping Babe (Vzygranie Mladenca) is but one among many. But what is its origin and meaning? Is it merely sentimental – or is there something more than just a description of a little child joyful in it’s mother’s arms? Does it have a deeper theological meaning?

Before we deal with these questions, let stay for a moment with the Chevetogne icon and consider it’s history, it’s iconography and to what ‘iconographical type’ it belongs.

ICONOGRAPHICAL TYPE AND INSCRIPTIONS

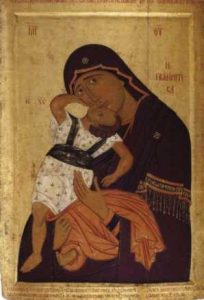

The icon of the Leaping Babe (or Playful Child) is one of the many variants of the type known by historians as the Virgin of Tenderness (in Greek Eleousa or Glykophilousa; in Russian Umilenie) . In this case the Mother of God carries the Child Jesus on her right arm. With inclined head, her cheek touches that of her child who, in his turn, caresses his mother’s chin and looks into her eyes. In his other hand the child holds a scroll symbolizing the Word of God.

The icon with an oklad.

Postcard from the 1930

The icon bears the traditional inscriptions MP ΘY, Meter Theou, for Mother of God and IC XC, Iesous Christos, for Jesus Christ, and also the epithet Vzygranie Mladenca (the Leaping of the Child) and the iconographer’s signature on the lower border: «This holy image was renewed (obnovlen) in 1703, painted by the tsar’s zograph Cyril Ulanov» .

Until the fifties of the twentieth century the icon was covered with an oklad of late date and little value. It covered the ground and the borders but left the image itself and the inscriptions free. An old post card from the 1930s is evidence of this.

ORIGINAL WORK OR RESTORATION?

What does the signature on the lower part of the icon tell us? The words obnovlen (literally: renewed) and obnovlenie (renewal), when used in connection with icons, can have several meanings:

1. It can indicate the icon’s «invention», i.e. its discovery, its first appearance, often miraculous, in a particular location. This invention is the origin of a local cult of veneration and a new name (toponym) for the icon.

2. Sometimes the word refers to the icon’s dedication, its inauguration or its benediction during an office. It is in this sense that it is employed also for the dedication of a church (in Greek: egkainismos).

3. Finally, it can be rendered as the restoration, the renovation or the repainting of an old, damaged icon. There are even certain cases, if the icon is beyond recovery, where the painter is free to use the panel on which to repaint an entirely new icon .

In our case it clearly means renovation in the full sense of the word rather than the minimal restoration that might be done today. Of the sixty or more surviving works of Cyril Ulanov, two are signed in the same way as the Chevetogne icon. In both cases it evidently means the renovation of the ancient icon in the style of the period, a restoration that conserved only the basic outline, the underlying plan of the icon. It is difficult sometimes to know exactly the state of the original icon, even using the most modern techniques, and to know to what extent the painter has changed the original icon. Furthermore, it should be noted, at this period (end of XVIIth – beginning of XVIIIth century), the same icon-painter could paint in quite different styles, sometimes more traditional, sometimes more modern .

In the present case it is interesting to compare the Chevetogne Vzygranie Mladenca with other icons of the Mother of God entirely painted by Cyril Ulanov. On the latter there is more contrast in the play of light and shade and there is a greater variety of colour. We find there, for example, the same gentle looks and the same mother- child relationship as on our icon. However, it is in the finish, in the details and most notably in the icon’s look that we recognize the hand and spirit of Ulanov.

THE “ZOGRAPH TO THE TSAR” CYRIL ULANOV

So what do we know about this iconographer who bears the title «Zograph to the Tsar»? Cyril Ulanov came from a family of iconographers from Yurevets, a small fortified village on the Volga, half-way between Kostro-ma and Nizni-Novgorod. His brother Basil and his son Ivan, both also icon-painters, regularly collaborated with him according to normal practice. We have no indication of the date of Cyril’s birth, but we do know that by 1688 he was working as a master painter in the Armoury Palace in Moscow. From the beginning of the XVIth century the Armoury Palace (Oruzheynaya Palata) housed all those workshops producing necessary goods for the tsar. It was here that arms, clothing, tableware, icons, jewelry and all kinds of precious objects were manufacture by the finest craftsmen in the land. Very soon the young Cyril won admiration and praise for his mastery. There he learned the new ‘nearer to life’ (zivopodobnyj) style of icon-painting that had been introduced by Simon Ushakov. However, he never turned his back on traditional iconography. He was commissioned to paint icons and whole iconostases for chapels and private residences in the tsar’s court, for the cathedral of the Dormition in the Moscow Kremlin, for sanctuaries and monasteries adjacent to the capital and further afield: Vologda, Novgorod, Kiev, even Moldavia (Suceava, Humor, Radaui).

However, towards the end of the XVIIth century political and cultural circumstances began to change. Certain of his patrons were dead or imprisoned. Henceforward there would be fewer court commissions. By 1701 there remained only two icon painters in the Armoury Palace, Cyril Ulanov and Tikhon Filatiev (+ 1731). When Peter the Great disbanded the Armoury Workshops in 1702, some of the craftsmen established themselves in the new capital, Saint Petersburg; others dispersed. Cyril Ulanov became an independent icon-painter. His son and pupil Ivan, icon-painter to the tsarevitch Alexis, stayed in Moscow. Cyril, now a widower, became a monk under the name Korniliy (Cornelius) at Krivoezerskaya Pustyn (the Desert of Krivoezerskaya) near the village of his birth. This small monastery on the Volga, alas, no longer exists. It was closed in 1917 and disappeared completely in the mid 1950’s in an artificial lake, the Gorki Reservoir. Two of Isaak Levitan’s most admired paintings, The Quiet Abode (Tikhaya obitel’, 1890), and Evening Bells (Vecherniy zvon, 1892), together with some old postcards, keep the memory alive.

Isaak Levitan, Quiet Abode, 1890,

The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Isaak Levitan, Evening Bells, 1892,

The Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

This unassuming provincial monastery provided our icon-painter with a new environment for his work; it was a much calmer place than the Armoury Workshops and it freed him from economic concerns. To celebrate the fortieth day of his profession as a monk Korniliy Ulanov painted his first icon for the monastery: a «Mother of God of Jerusalem», which later came to be considered a miraculous icon. It was destroyed during the Russian Revolution by a defrocked monk of the monastery, a former political prisoner of the tsarist penal colonies.

Krivoézerskaja Pustyn’

In 1714, after five years in the monastery, Korniliy was elected superior of the small community. From that time on his work was mainly directed towards the monasteries and churches in the surrounding area. Shortly before his death, he withdrew from the role of hegumen (abbot) to take on the angelic habit (Great Schema) under the name of Karion. He died in 1731 at an advanced age. His tomb disappeared at the same time as the monastery church.

THE CHILD LEAPED IN HER WOMB

Let us now return to our icon Vzygranie Mladenca. The name is usually associated with another, later (XIVth century) variant of the Mother of God of Tenderness also known by its Greek name Pelagonitissa, after it’s place of origin, Pelagonia, in Macedonia. “Here equally” – writes Andre Grabar – “the faces of both mother and child touch cheek to cheek, but the position of the child is different: with somewhat agitated movement, he is upright on his mother’s knees and, turned towards her, his head thrown back, he presses his head against his mother’s chin. He caresses Mary’s cheek with his left hand while she, in her turn, holds him by one of his legs” .

Pelagonitissa 1491-2,

Macedonian Museum, Skopje

We can say that icons and iconographic types existed before particular names were assigned to them and often the names were known long before their inscriptions appeared on the icons themselves. Originally the inscriptions on icons were minimal and nearly always the same, regardless of geographic origin or iconographic type: MP ΘY for the Mother of God, IC XC for the child Jesus. These inscriptions served to identify the persons and to endorse our faith in them: the «Mother of God», «Jesus Christ» (=Jesus, the Messiah). Thus, the names Eleousa (Merciful) or Umilenie (Tenderness) are not found on the oldest icons of the Virgin. It is from the beginning of the XIIIth century that titles, derived from liturgical or patristic sources, were first inscribed on icons of the Virgin; names «that applied not to the iconographic types, whatever they were, but to the person of Mary herself. Consequently, they remained applicable regardless of which image of the Theotokos” . The same iconographic type could thus have different epithets and change its name according to place or time. The name on an icon is not an explanation of its iconographic type. It is not an expression of what we see in an icon. Rather, it expresses our belief in the subject or the person represented. It is not the picture’s «title» or subject. It is a confession of faith.

This is manifestly true also for the icon Vzygranie Mladenca.

Here, admittedly, the epithet does also describe what we see on the icon: a child exulting in his mother’s arms. This is why the eminent Russian art historian, Victor N. Lazarev, calling it «the Mother of God with the Playful Child in Her Arms», gave, perhaps inadvertently, too restricted a meaning to Vzygranie Mladenca. On the one hand, as the icon of Cyril Ulanov at Chevetogne clearly demonstrates, the child Jesus does not ‘leap’ on many of the icons of that name. On the other hand, the epithet does indicate more to us than what we actually see. It speaks also of what we believe, knowing that the child’s joy comes to him from his mother. She is the fountain of joy, its creator and its cause .

But can we not go further? The thrill of joy animating the child Jesus, this joy that comes to him from his mother – even though we may believe it – has no biblical foundation. In the New Testament it is another child who starts with joy at the approach of the Mother of God, namely Saint John the Baptist at the moment of the Visitation of Mary and Elisabeth. The story is told in the gospel of Luke (Lk 1, 29-49, 56) and read at Matins in the Orthodox Church on all the great Marian feasts:

«Thus, when Elizabeth heard Mary’s salutation, the child leaped in her womb [vzygrasja mladenec vo čreve eja] and she was filled with the Holy Spirit. And she cried out in a loud voice saying: ‘blessed art thou among women and blessed is the fruit of the womb. And whence is this to me that the mother of my lord should come to me? For lo, as soon as the voice of the salutation sounded in my ears, the babe in my womb leaped for joy [vzygrasja mladenec radoscami vo čreve moem]. And blessed is she that believed: for there shall be a performance of those things which were told her from the Lord’« (41-45).

This biblical passage, very well known through the liturgy, is the only place in all of the New Testament where the word translated (in the Authorised Version) as ‘leaped’ (vzygratisja in Slavonic, skirtao in Greek) is used – and furthermore, only twice – in relation to the child. The name Vzagranie Mladenca, therefore, can only come from this gospel passage. Its meaning can be formulated as follows: Mary is the ‘joyful impulse’ for every child, even before his birth, when this child’s mother (Elisabeth in the gospel account), recognizes in Mary the «Mother of my Lord» who comes to her meeting .

In other words, to recognize that Mary is the child’s impulse is equivalent to confessing that she is the «Mother of my Lord»; at the same time it is the recognition that she is the Mother of God (the Theotokos) and that the Child who is born is my Lord. It is thus also to recognize oneself – with joy – as a child of God.

The icon Vzygranie Mladenca, which the Russian church celebrates on 7th November, is thus more than just a touching image of the relationship between a mother and her child. It is our confession of faith in the incarnation, our belief in salvation. It is the faith we find in the joy of being children of God. It is this that the troparion composed by Father Denis Guillaume especially for the icon by Cyril Ulanov at Chevetogne wished to express:

“You delight the Child you carry in your arms and you are equally the cause of exultation of him who leaped in his mother’s womb when you greeted your cousin Elisabeth. Now that Christ has made us your children enable us, even us, to find in you, in contemplating your icon and venerating it, the joy and the promise of our souls”.

(Author: Antoine Lambrechts, translation from Dutch by Richard Temple, London Temple Gallery)